I was 10. My mom was at the hospital. My dad ordered us, kids, to play outside. An hour later, he announced we were going to Burger King. When we got home, he sent us straight to bed. Later that night, when I was creeping out of bed to get some water, I found him sitting on the living room floor, holding her wedding ring in one hand and a crumpled hospital bracelet in the other. He was crying like I’d never seen before—silent, shaking, like the world had caved in.

He didn’t hear me. I stood there, frozen in the hallway, bare feet cold on the tile. I didn’t understand everything, but I knew something had changed. My mom was sick. Sicker than he had let on.

The next morning, the house was quiet. No one made pancakes. No cartoons. Dad didn’t even yell for us to get dressed. He just sat at the table, his hands wrapped around a coffee mug he hadn’t touched. My older sister, Nira, gave me a look like, don’t say anything. So I didn’t.

A few days later, we were told Mom was “resting for a while” and wouldn’t be home just yet. I asked if I could visit her. Dad looked like he wanted to say yes, but instead he said, “Not today, little man.” His voice cracked. I never asked again.

Weeks passed. Nira stepped into this weird half-mom role—making toast, brushing our sister Priya’s hair, even doing laundry. She was only thirteen. I started wetting the bed again. Dad didn’t scold me. He just quietly changed the sheets when he found them. That scared me more than if he’d yelled.

Then one afternoon, Dad picked us up early from school. He didn’t say why. Just told us to get in the car, and we drove in silence to a park on the edge of town we’d never been to before. He pulled out a Tupperware of peanut butter sandwiches, handed them out, and sat down on a picnic bench.

“I wanted to tell you all together,” he said. “Your mom’s not coming home.”

The world tilted.

I remember Priya dropping her sandwich. I remember Nira going stiff like someone turned her to stone. I don’t remember what I said. I just remember running. Somewhere, anywhere. I ended up in the men’s bathroom, sitting on the cold concrete floor, trying to breathe.

After that, everything was just… different.

The house felt too big. Too quiet. Dad did his best, but grief sucked all the air out of him. He burned dinners, forgot to sign school forms, and sometimes just didn’t come home from work until after we were asleep. He left notes on the fridge like, Dinner in freezer. Love you.

One night, I heard him yelling on the phone. It was the first time in months he’d raised his voice. Something about rent and “I can’t keep doing this alone.” I peeked from the hallway. He was pacing, phone pressed so hard to his ear it looked painful. Then he threw it. Just straight-up launched it across the kitchen. I didn’t sleep that night.

The next morning, there was a woman in our kitchen.

She wore a navy-blue sweater and had short, curly hair. She smiled at me like she knew me. “You must be Anil,” she said. “I’m Maritza. Your dad and I went to college together.”

She made eggs. Real ones, not microwaved. She sat with us and asked what cartoons we liked, how school was going, if we had pets. I didn’t answer. Neither did Priya. Nira answered with sharp, clipped words.

That night, Maritza was still there. She tucked Priya in. I saw her kiss Dad on the cheek. And just like that, our mom’s name stopped being said out loud.

Maritza moved in three weeks later. Her toothbrush beside Dad’s. Her shoes near the door. She brought over this lemony candle that made the whole house smell like spring. I hated it.

Then came the rules. New food. New bedtimes. She made us write in journals every night—“to process feelings.” She took our TVs out of our rooms and made us do Saturday chores like we were in a boot camp. And every time I looked at her, all I could think was, You’re not Mom.

One night, I told her that.

She froze. Her face didn’t change, but her eyes did. “I know I’m not,” she said quietly. “And I never will be. But I’m here. That counts for something.”

I didn’t say anything back. But I noticed she stopped tucking me in after that.

Years passed. Nira left for college, then barely came home. Priya went full goth and got her nose pierced at 15. I started skipping school, failing math, lying to teachers. Maritza tried to “connect” but everything felt fake. Her voice too calm, her hugs too rehearsed.

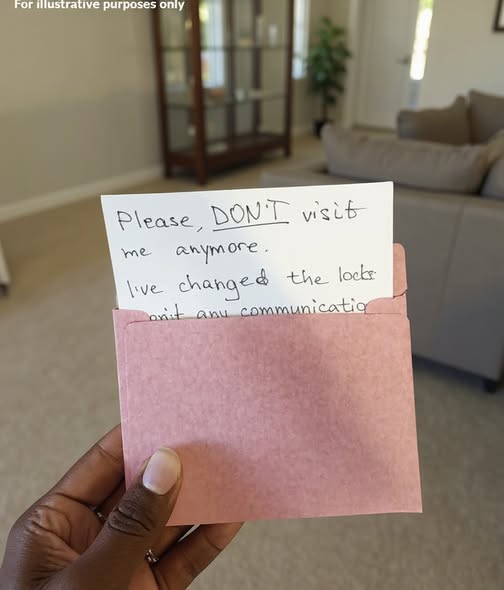

Then senior year, I found something.

I was digging through the basement for an old yearbook. Instead, I found a locked box wedged behind the furnace. Small, metal, dusty. Of course I opened it. The lock popped with a butter knife.

Inside were letters. Dozens. Some addressed to “Maritza,” some to “Rohan,” my dad. All from the same sender: Amara. My mom.

The dates were recent. One as late as six months ago.

My brain stuttered.

I read one. Then another. My mom was alive.

Not just alive—writing, begging, pleading to see us. She talked about rehab, about getting better, about knowing she’d made mistakes but wanting to explain. She said she’d respected the court’s no-contact order but missed us so much it physically hurt.

I felt sick.

I confronted my dad that night.

He didn’t deny it. Just stared at the table like it was trying to swallow him. “I was trying to protect you,” he said.

“From what?”

“From being disappointed again.”

Turns out, my mom had struggled with addiction. After a surgery gone wrong and a prescription she got hooked on, things spiraled. She missed pickups, forgot meals, scared Priya once by falling asleep with the stove on. That last one was the final straw. Dad filed for full custody. Mom disappeared into rehab.

We’d been told she died because, in a way, she had. To him.

But she hadn’t. She’d been writing letters. Wanting a second chance. And he’d never shown us a single one.

I moved out the next month. Crashed on Nira’s couch while I figured things out.

Then I wrote a letter. Not to my dad. To my mom.

I didn’t know if she still lived at the address on the envelopes. But I wrote it anyway. Told her I was alive. Told her I remembered her singing while she cooked, how her hair always smelled like coconut. I told her I wanted to meet.

Three weeks later, I got a reply.

And two months after that, I was sitting in a little café in Detroit, across from the woman who gave birth to me. She looked older, thinner, more tired. But when she smiled, my whole body lit up in recognition.

We talked for three hours.

She told me everything. The pills. The mistakes. The nights she didn’t think she’d make it. But also the recovery. The sobriety. The work she’d done. She’d become a counselor now, helping other women climb out of the same hole.

“I wasn’t ready then,” she said. “But I am now.”

Rebuilding wasn’t easy. It wasn’t quick. But we started.

Small things. Birthday calls. Texts when the Lions won. She sent me a homemade scarf that winter, yellow and lopsided. I wore it every day.

Priya didn’t want contact. Nira was furious at first, but softened eventually. Me? I kept going back. Kept showing up.

Maritza reached out once. A long email, saying she was sorry for everything. That she hadn’t known about the letters until later, and she had tried—really tried—to help hold our broken family together. I didn’t know how to respond. I still don’t.

Years later, I invited both my mom and my dad to my wedding.

It felt weird. But also right. They sat on opposite ends of the second row, quiet, respectful. Maritza didn’t come, but she sent a gift—an old photo of me as a baby with both my parents smiling. Framed in wood.

After the reception, my dad came up to me. He looked older. Smaller somehow.

“I’m proud of you,” he said. “And I’m sorry. For everything.”

I hugged him.

Some pain never goes away. But it softens. Fades around the edges. Becomes something you can carry.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s this: people mess up. In huge, horrible ways. But when someone reaches for you—with real humility—you don’t always have to slam the door. You can crack it. Just a little. Let some light in.

If you’ve ever lost someone—by death, addiction, betrayal, silence—know this: the story doesn’t have to end there.

Sometimes, it’s just starting again.

If this moved you, give it a share or a like. You never know who might need it today.